What Der Blaue Reiter Brought With Itself to Art History

Feb 11, 2019

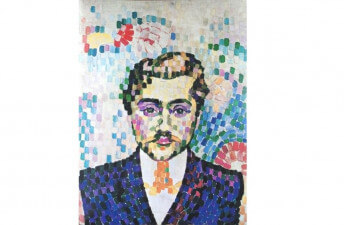

German Expressionism, which emerged around 1905 and thrived until the late 1920s, was one of the most influential aesthetic movements of the 20th Century. The movement has its roots in two distinct groups: Die Brücke (The Bridge), and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Both groups focused on setting artists free to express their inner realities, but they differed in subtle ways, both philosophically and aesthetically. Die Brücke developed a visual language similar to that of woodcut prints, using large areas of pure color and primitivist lines. Die Brücke artists also tended to use people as their primary subjects. Der Blaue Reiter artists developed a softer, more lyrical aesthetic, using organic shapes and forms, and painting with fewer hard edges. For their subject matter, Der Blaue Reiter sometimes painted people, but turned mostly to animals and the natural environment, interests that they felt conveyed the spiritual side of human existence. Eventually, membership in Der Blaue Reiter included at least nine artists: Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Henri Rousseau, Robert Delaunay, Alfred Kubin, Gabriele Münter, Paul Klee, and the composer Arnold Schoenberg. Its two primary founders were Kandinsky and Marc. According to Kandinsky, he and Marc came up with the name Blue Rider while sitting together at a cafe. Marc said that he liked horses, which to him symbolized the free creative spirit of nature, and Kandinsky responded that he liked riders, which symbolized the artist trying to control the creative force. Marc thus established himself as the energetic, creative leader of the group, and Kandinsky became the one to whom they looked for theoretical guidance. The writings Kandinsky produced around this time about spiritualism and aesthetics went on to help shape the entire modern and contemporary evolution of abstract art, and they were especially influential on the artists of Der Blaue Reiter. Kandinsky wrote that how we feel about something in our soul is as important, or more important, than how we perceive it visually. The soul, Kandinsky wrote, “can weigh colors in its own scale and thus become determinant in artistic creation.” Reading these words, the optimism of Der Blaue Reiter is evident, making it all the more tragic that the emergence of the movement occurred just when the darkest period of human history was on the horizon.

The Blue Rider Almanac

Like many European aesthetic movements that evolved alongside it, German Expressionism was largely a reaction against Impressionism. Ironically, when it began, Impressionism was revolutionary, brushing off the shackles of realism and embracing the notion that artists could paint impressions of the world, not just imitations of it. But as Impressionism became the new standard style, various Post-Impressionist movements challenged it. German Expressionists were not satisfied painting impressions of the world. They sought to translate their inner experiences of life. They demanded total freedom from style, and worshipped the individual creativity of the artist. Part of the reason they made such demands was because of the angst they felt in the wake of rapid social industrialization. Traditional ways were disappearing and the structures that regulated society were losing power. Realistic art had little value in such a world. The Expressionists knew the only way they could add anything to the changing world was to discover ways of making art that was radically unique.

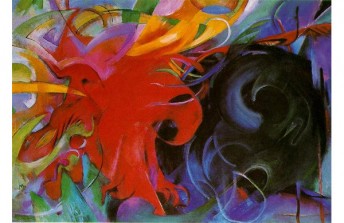

Franz Marc - Fighting forms, 1914. Oil on canvas. 91 x 131.5 cm (35.8 x 51.7″). Pinakothek der Moderne.

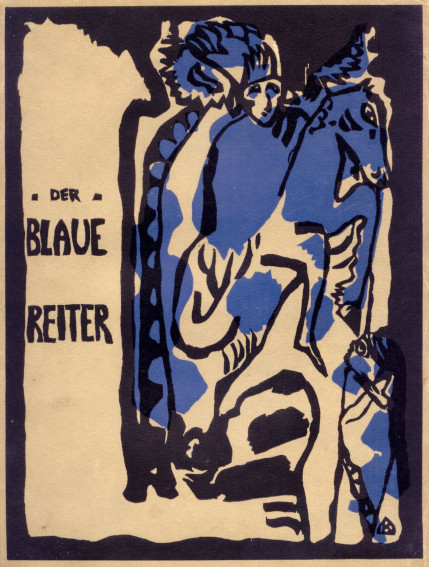

Yet when Kandinsky and Marc founded Der Blaue Reiter, they did not pretend to be completely original. They saw examples of other artists throughout history who had embraced freedom and individual creativity. From the artists of Africa and Asia, to contemporaneous artists like Matisse, to artists of other disciplines such as composers, they found inspiration everywhere. They published a book in 1912 called The Blue Rider Almanac. Within its more than 120 pages are photographs, texts, drawings, and musical notations outlining the multitude of influences that had guided their thinking. The book tells the story of two artists who perceived soulfulness and beauty in the world, and longed to contribute to its legacy.

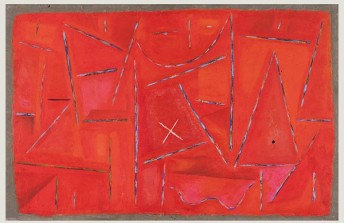

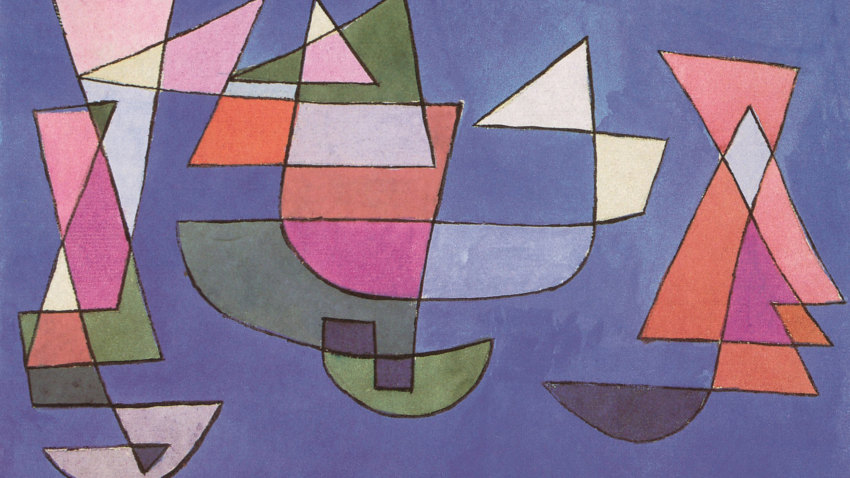

Paul Klee - Sailing Boats, 1927. Watercolour on paper mounted on cardboard. 22.8 x 30.2 cm, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern.

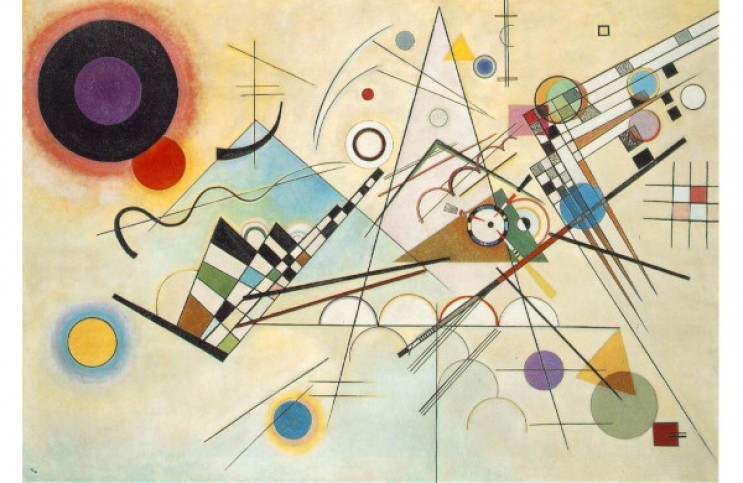

Ultimate Reduction

All of their various influences led Kandinsky and Marc to understand that everything in life is made up of smaller things. What makes up a landscape? Trees, grass, the sky, animals, but also the relationships between all of those things. What makes up a song? Individual notes, rhythms, melodies, and beats, but also the relationships between those parts. What makes up a picture? Lines, colors, shapes, gestures, planes, masses, volumes, space, surfaces, textures, and of course all of the countless changing relationships between each of these things. One key for Der Blaue Reiter became reduction—the goal of taking what they saw and experienced and uncovering its universal underpinnings. Kandinsky, more than any of the others, saw reduction as the way forward towards total abstraction, believing that each individual visual element was valid in itself, and held the same potential emotive power as each element of nature, or each element of a song.

>

>

Wassily Kandinsky - Cover of Der Blaue Reiter almanac, c. 1912.

Der Blaue Reiter showed their work in only three exhibitions before disbanding. Unlike Die Brücke, they did not disband because of the egos and ambitions of the individual members of the group. Rather, they were ripped apart by World War I. Both Macke and Marc were drafted into the German army. Right before going to war, Macke painted his last work, a somber composition of faceless mourners titled “Farewell.” He died weeks later on the front lines. Marc served in the infantry as well, transferring two years later to the camouflage unit, where he painted German tents to look like Kandinsky paintings to make them invisible from the air, and later died from shrapnel wounds. Kandinsky, meanwhile, was forced to leave Germany and return to Russia. After the dissolution of Der Blaue Reiter, German Expressionism continued to evolve for decades after the war, becoming darker and more cynical all the time. Der Blaue Reiter lives on as one of its more enduring and formative moments, representing not only the importance of inner vision, but the potentialities of abstraction, and the power of the human will to freedom.

Featured image: Wassily Kandinsky - Composition VIII, 1923. Oil on canvas. 55.1 × 79.1" (140.0 × 201.0 cm). New York, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio