Female Abstract Painters of Color Finally in a Museum Show

Sep 6, 2017

If you have not yet had a chance to see it, a fascinating and engaging exhibition closing soon at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary art in Kansas City, Missouri, is guaranteed to please your senses and challenge your knowledge of art history. Female abstract painters of color are the focus of Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today. The exhibition defies the existing canon of American abstract art history, which has long been dominated almost entirely by stories of brilliant white men. And even in those rare instances when the stories of female abstract painters were told, they were almost exclusively the stories of white women. Those who had a chance to visit the recent landmark exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism, which was hosted in 2016 by the Denver Art Museum, surely also noted that even that show failed to pay equal respect and attention to female abstract painters of color. It would have been simple to include to its ranks an artist like Mildred Thompson, who was alive and working in the Abstract Expressionist style in New York in the 1950s. The sad fact is that if one were to gauge the topic simply by what museums and galleries have shown in the past, it would be easy to assume that prior to the last 40 years or so, there never were any female painters of color in America working in the field of abstraction. Happily, this exhibition, co-curated by Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina, begins the long process of putting all of those fallacies to rest. Featuring the work of 21 American female abstract painters of color, the show takes a vital first step toward finally setting the historical record straight.

Where Have You Been All Our Lives?

One of the most highly anticipated works on view in Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today is a painting by Mavis Pusey, titled Dejygea. Painted in 1970, the work last appeared in public in an exhibition titled Contemporary Black Artists In America, which was held at the Whitney Museum in New York in 1971. It is now part of the permanent collection of the Kemper Museum. In addition to being the perfect anchor for this show, the work is perfectly representative of the energetic, dynamic form of geometric abstraction for which Mavis Pusey is known. With roots in Suprematism, Constructivism, Futurism and Hard Edge abstraction, Pusey has created an expansive oeuvre that excels in complexity and visual impact beyond many of her contemporaries, and some would say beyond many of her influencers. Unique to her aesthetic approach is her desire to express the specific blight and rebirth of the urban sphere, as the forms and colors in her pieces relate specifically to the growth cycles of the city. I was not new to her work prior to this exhibition, but now that I have been reminded of her contribution by this show I intend to seek out more examples of her work.

One heritage artist featured in magnetic Fields whose work was completely new to me is Howardena Pindell. Born in 1943, she received her MFA from Yale in 1967. Early in her career she worked at MoMA in New York as an associate curator. Like many of the artists in this exhibition, she created most of her oeuvre while holding down a full time job. She is still active today at age 74 in Philadelphia. Her layered, dimensional abstract works fold in on themselves while exploding outward. They speak in conversation with biomorphism and the Korean abstract art style known as Dansaekhwa. Currently a teacher at Stoney Brook University in New York, Pindell has exhibited extensively throughout her career. Remarkably, I have been to many of the museums in which her work is part of the permanent collections. But somehow I have never encountered a single piece by her. It is completely unfamiliar to me. Have I just not noticed it? Or is it not on display? The work possesses a unique aesthetic position, and hopefully due to this exhibition will be shown more often.

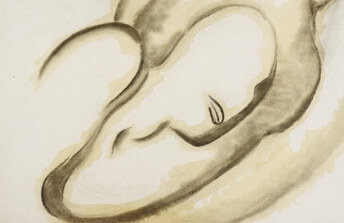

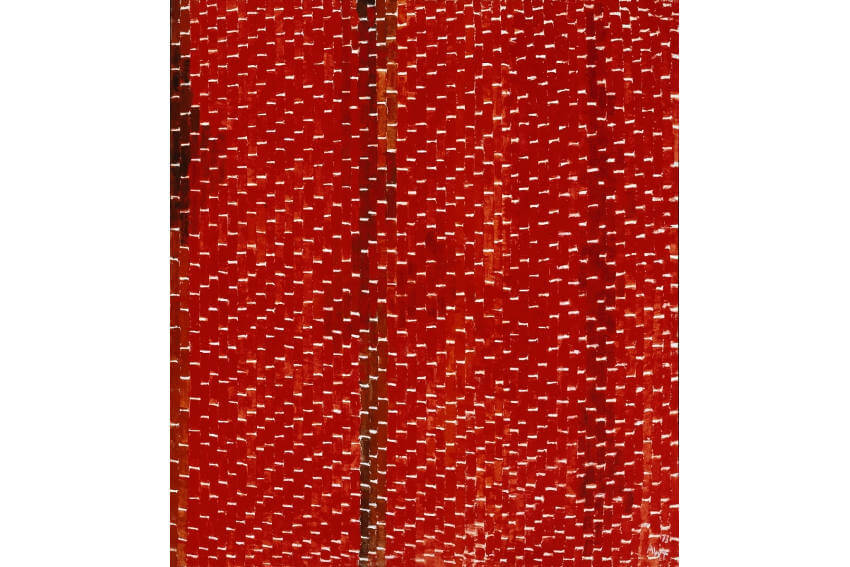

Alma Woodsey Thomas - Orion, 1973, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 54 inches, courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. © Alma Woodsey Thomas, photo by Lee Stalsworth

Alma Woodsey Thomas - Orion, 1973, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 54 inches, courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. © Alma Woodsey Thomas, photo by Lee Stalsworth

The Younger Generation

Of course, a major part of Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today is the word today. Among the younger contemporary black American female abstract artists whose work is on view in the exhibition are three extremely well known artists: Chakaia Booker (b. 1953), Brenna Youngblood (b. 1979), and Shinique Smith (b. 1971). The iconic tire sculptures of Chakaia Booker are well known to most contemporary art enthusiasts, and enjoy a rightful place in many museums as well as in the public art collections of many cities. I have written about Brenna Youngblood in the past. Her haunting, textured paintings add what are sometimes the smallest figural elements, bringing a dreamlike quality to the composition. Her use of color and mastery of harmony is sublime, and the complexity of her surfaces invites the eye to keep staring and staring. And I am also very familiar with the powerful work of Shinique Smith. Inhabiting a mid-space between sculpture, painting and installation, it makes a definitive contemporary statement. New to me among the younger generation of contemporary artists in this exhibition was Abigail DeVille (b. 1981), whose dramatic, multi-faceted, sculptural installations place her in an aesthetic heritage with Louise Bourgeois. While coming across as uniquely personal in some respects, the stunning works DeVille creates also speak in broad ways to a larger culture of decay, rebirth, pain and survival. Also new to me was Nanette Carter (b. 1954), whose latest body of work, oil on mylar and metal paintings, speak in interesting conversation with Synthetic Cubism, assemblage art and DaDa collage. Also new and notable to me was the elegant, pared down work of Jennie C. Jones (b. 1968). The paintings she makes have a sort of sculptural presence that is confident and strong, and yet so soothing to be around. They evoke the aesthetic language of Modernist history while also presenting something fresh and clearly contemporary.

Shinique Smith - Whirlwind Dancer, 2014–2017, ink, acrylic, paper and fabric collage on canvas over wood panel 96 x 96 x 3 inches, collection of Leslie and Greg Ferrero, courtesy of David Castillo Gallery, Miami, photo by E. G. Schempf; © Shinique Smith

Shinique Smith - Whirlwind Dancer, 2014–2017, ink, acrylic, paper and fabric collage on canvas over wood panel 96 x 96 x 3 inches, collection of Leslie and Greg Ferrero, courtesy of David Castillo Gallery, Miami, photo by E. G. Schempf; © Shinique Smith

The Black Abstract Aesthetic

In addition to putting to rest the tired notion that black American females did not participate in the abstract art movements of the 20th Century, Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today also brings to light several other issues related to racial and gender identity and abstract art. It raises questions about all of the various forms of prejudice that existed in the past, and still exist, when it comes to the idea of abstraction as a relevant way to express a culturally-specific point of view. For example, another exhibition currently on view at the Tate called Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, focuses specifically on the art that emerged out of the Black Arts Movement that began in the United States in the 1960s. The vast majority of the work in the show is figurative, but there are some abstract works included. Among those abstract works are pieces by Martin Puryear, John Outterbridge, and William T. Williams. But it is noteworthy that the relatively few works by females that are represented in the show are almost entirely figurative. In general, abstraction was often excluded from exhibitions that represented the Black Arts Movement, perhaps not because of any implied sense of its validity, but just because there was a political side to the movement that found figuration more useful toward achieving its goals. Incidentally, it is worth noting that there is a piece in that show at the Tate by Andy Warhol: about as white of an artist as could be imagined. What that means, I do not know. But to think that the curators chose a Warhol over a work by a black female abstract artist who was working at that time, such as Alma Woodsey Thomas or dozens of other, shows just how far the art world still has to go before it fully acknowledges the contribution of the female abstract painters of color.

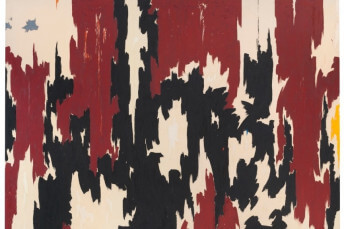

Mildred Thompson - Magnetic Fields, 1991, oil on canvas, triptych 70.5 x 150 inches, art and photo courtesy and copyright of the Mildred Thompson Estate, Atlanta, GA

Mildred Thompson - Magnetic Fields, 1991, oil on canvas, triptych 70.5 x 150 inches, art and photo courtesy and copyright of the Mildred Thompson Estate, Atlanta, GA

Also On View

In addition to those featured in this article, the other wonderful artists included in this exhibition are Candida Alvarez (b. 1955), Betty Blayton (b. 1937, d. 2016), Lilian Thomas Burwell (b. 1927), Barbara Chase-Riboud (b. 1939), Deborah Dancy (b. 1949), Maren Hassinger (b. 1947), Evangeline “EJ” Montgomery (b. 1930), Mary Lovelace O’Neal (b. 1942), Gilda Snowden (b. 1954, d. 2014), Sylvia Snowden (b. 1942), Kianja Strobert (b. 1980), Alma Thomas (b. 1891, d. 1978), and Mildred Thompson (b. 1936, d. 2003). Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today is on view through 17 September 2017 at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, MO, after which it will travel to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., where it will be on view from 13 October 2017 through 21 January 2018.

Mary Lovelace O’Neal - Racism is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere, 1993, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 86 x 138 inches, photo courtesy of the Mott-Warsh Collection, Flint MI. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal

Mary Lovelace O’Neal - Racism is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere, 1993, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 86 x 138 inches, photo courtesy of the Mott-Warsh Collection, Flint MI. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal

Featured image: Magnetic Fields - Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today, installation view at Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio